Captain Future #11: Treasure on Thunder Moon , livre ebook

52

pages

English

Ebooks

2018

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

52

pages

English

Ebooks

2018

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Publié par

Date de parution

30 juillet 2018

Nombre de lectures

2

EAN13

9788828366096

Langue

English

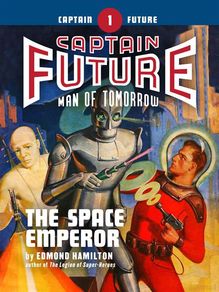

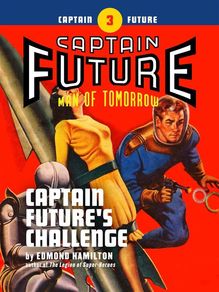

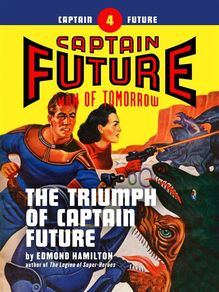

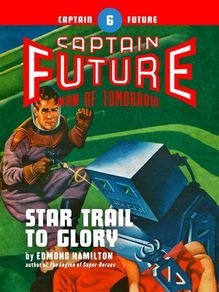

The Captain Future saga follows the super-science pulp hero Curt Newton, along with his companions, The Futuremen: Grag the giant robot, Otho the android, and Simon Wright the living brain in a box. Together, they travel the solar system in series of classic pulp adventures, many of which written by the author of The Legion of Super-Heroes, Edmond Hamilton.

Publié par

Date de parution

30 juillet 2018

Nombre de lectures

2

EAN13

9788828366096

Langue

English

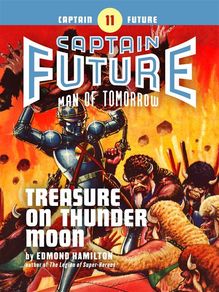

Treasure on Thunder Moon

Captain Future book #11

by

Edmond Hamilton

It’s hell to be told 37 is too old to fly the void when you know where a great treasure lies!

Thrilling

Copyright Information

“Treasure on Thunder Moon” was originally published in 1942. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Chapter I

The Company

“MAYBE there’s a chance,” John North thought desperately. “If they just don’t think I’m too old—”

North’s small, compact figure, shabby in a frayed black synthe-wool suit, threaded between the docks of towering space liners and through hurrying officials, swaggering young spacemen, and sweating porters, until he reached the impressive offices of the Company.

The operations office of the Interplanetary Metal and Minerals Company, that giant corporation known everywhere as simply “the Company,” was a massive block of glittering chrom-aloy. Beyond it lay the towering warehouses and docks and cranes that handled the cargoes from other worlds.

John North paused outside the entrance to inspect his reflection in the polished metal wall, earnestly smoothing his worn jacket. His heart sank as he looked at his own image. His dark hair was faintly thin at the temples, his black eyes had tired lines around them, his tanned face looked thin and pinched and old.

“Thirty-seven isn’t old!” he told himself fiercely. “Even for a spaceman, it’s not old. I’ve got to look young, feel young!”

But it wasn’t easy to feel young, with the hunger he had felt all afternoon gnawing at him, with foreboding of failure gripping him, with his shoulders sagging from twenty years of toil and hardship and heartbreak.

“Straighten up—that’s it,” North muttered. “Look spruce, alert, efficient. And smile.”

Yet he couldn’t keep the mechanical smile on his drawn, old-young face as he made his way through busy chrommium corridors to the office of the new operations manager. He waited there for what seemed an eternity, fighting the hunger-born dizziness that threatened him. At last he was admitted.

Harker, the new manager, was a gimlet-eyed, tight-mouthed man of forty who sat behind a big desk reading off a materials list to a respectful young secretary. He looked up impatiently when North nervously cleared his throat.

“John North, sir, applying for a berth,” North stated, trying to look the picture of a clean-cut efficient spaceman. “I’m a licensed S.O.”

“Space Officer, eh?” said Harker. “Well, we can use a few good pilots now on the Jupiter run. Let’s see your certificate.”

It was the moment North had dreaded. Slowly he handed over the frayed, folded document. His shoulders sagged slightly as he waited.

The manager turned the frayed certificate over, his gimlet eyes starting to read the service-record on its back. He looked up suddenly.

“Thirty-seven years old!” he snapped. He tossed the document onto the desk. “What did you come in here for? Don’t you know that the Company never hires a man over twenty-five?”

John North tried hard to keep his mechanical smile. “I could be valuable to the Company, sir. I’ve had twenty years space experience.”

“That’s fifteen years too much,” answered the manager brutally. “A spaceman’s washed out at thirty. He doesn’t have the coordination, quickness of reaction or alertness of a younger man. We don’t trust our ships to worn-out, middle-aged men who can’t meet emergencies.”

John North felt his faint hope expire. This new operations manager had the same viewpoint that all the others had had.

The young secretary was looking curiously at North. “You went to space twenty years ago? Why, that was in the earliest days of space travel. Half the planets hadn’t even been visited, then.”

North nodded dully. “My first voyage was with Mark Carew on his third expedition, in ’98.”

“And I suppose you think you’re entitled to a big job because you were a hero twenty years ago?” demanded Harker hostilely. “That’s the trouble with all you older spacemen. You think because you happened to be on the first exploring expeditions, because you got a lot of publicity and hero-worship then, that you all rate captain’s comets now.”

“But I don’t ask for a captain’s berth,” North protested. “It needn’t even be an officer’s post. I’ll take any job—a cyc-man, a tube-man, even a deck-hand.”

He added in strained appeal, “I need this job, a lot. And space-sailing’s the only trade I ever learned.”

The manager snorted. “Too bad for you, that you didn’t learn another trade. Anyway, even if you were young enough, the Company wouldn’t want you. The old careless ways of you early spacemen are out, these days. Ships are operated scientifically now, with none of the hell-raising hit-or-miss tactics of you old timers. Things have changed.”

North bit his lips and looked out of the window to repress his feelings. His tired eyes fixed on the soaring metal shaft that rose in the sunlight beyond the square bulk of the Company’s warehouses.

It was the Monument to the Space Pioneers, that marked the spot where Gorham Johnson had returned from the first epochal space voyage years before. North’s mind went back to the day when he himself had come back with Carew and landed there, the madly cheering throngs, the sententious speeches.

“Yes,” North said dully. “You’re right. Things have changed.”

HE went out of the building blindly, clutching his useless certificate. Out in the sunlight and bustle of the spaceport, North paused.

The Venus liner whose big cigar-like bulk towered from its dock nearby was making ready for take-off. He could hear the staccato thunder of its tubes being tested. Passengers and porters and gray-jacketed Company officers were hurrying toward the ship. A few bewildered Venusians, white-skinned, handsome men, and one or two solemn native red Martians were in the throng. A band was beginning to play a gay, lilting tune.

North could remember when this had all been a bare field, twenty years ago. There had been nothing here then but the ramshackle hangar in which a score of eager young men had worked with crippled, indomitable Mark Carew to prepare an absurdly small and clumsy ship for the great voyage that was to add Saturn and Uranus and Neptune to the list of visited planets.

That was his trouble, North thought bitterly. He was always living in the past, the times twenty years ago when the world was young and the sun was bright, and all Earth was cheering him and his friends to new pioneering exploits.

“I’ve got to forget all that,” he told himself heavily. “I’ve got to quit brooding on the past. But what am I going to do?”

He hated to go back to the shabby rooming house over on Killiston Avenue. Old Peters and Whitey and the others were hoping so fervently that he’d be able to get a berth today. They all needed the money so badly.

He shrugged wearily. They’d have to learn the bad news some time. He plodded off the spaceport, his slight, shabby figure unnoticed amid the excited, gay throng that had gathered to witness the take-off of the liner.

Killiston Avenue was one of the ruck of shabby streets around the spaceport. Its drab spacemen’s lodging houses, drinking joints and cheap restaurants huddled like disreputable dwarfs under the shadow of the Company warehouses. North turned in at his own lodging house and tiredly climbed the dark stairs to the dusty garret which he and his comrades had shared for six months.

North found some of the others already there. Old Peters was there, of course, sitting in his makeshift wheel-chair and peering across the huddled roofs at the thunderous take-off of the Venus liner. He turned his white head.

“That you, Johnny?” he shrilled, his faded eyes peering. “I was just watchin’ that liner blast off. Sloppiest take-off I ever saw!”

The old man quavered on. “Cursed if these young spacemen don’t get worse every day. You ought to have seen the landin’ the Mars mail-boat made this mornin’. Why, when I was rocketin’, anyone who made a landin’ like that would have been kicked off the spaceport.”

North assented absently. He was used to old Peters. The old man had not been in a ship for fifteen years, but still never tired of dwelling interminably on the old days.

“We wouldn’t have stood for such spacemanship,” he grumbled on.

North turned. Steenie was coming up to him. Steenie was forty three, but he had the smooth face and bright blue eyes of a boy of fourteen.

“Do we take off again tomorrow, John?” he asked North eagerly.

“Not tomorrow, Steenie,” North answered gently. “Maybe the next day.”

And Steenie went back to his chair in the corner and sat smiling vacantly at them. He had smiled that way for years, ever since he had come home from Wenzi’s last voyage, a space-struck mental wreck.

JAN DORAK came up to North. A dark, heavy, stolid ex-spaceman, he looked inquiringly at North’s drawn face.

“Any luck, Johnny? The new Company manager—”

“Is like all the rest,” North answered wearily. “I’m too old.”

The others were drifting in—Hansen and Connor and big Whitey Jones. They had heard his words.

“Never mind, they’ll have to call us in someday soon,” muttered stocky Lara Hansen confidently. “They’ll find out they need us old-timers.”

“And anyway, I got a little job today and we’ll eat tonight,” declared Mike Connor. “Look, fellows—grub and synthebeer for everybody.”

Connor’s battered, merry red face was carefree as always as he showed his packages. Connor never had worried about anything, not even as Carew’s third officer on that disaster-ridden second voyage long ago.

But big Whitey Jones, a shock-head