Angels Watching Over Me (Shenandoah Sisters Book #1) , livre ebook

140

pages

English

Ebooks

2003

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Découvre YouScribe et accède à tout notre catalogue !

Découvre YouScribe et accède à tout notre catalogue !

140

pages

English

Ebooks

2003

Vous pourrez modifier la taille du texte de cet ouvrage

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Publié par

Date de parution

01 janvier 2003

Nombre de lectures

0

EAN13

9781441211378

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

2 Mo

Publié par

Date de parution

01 janvier 2003

EAN13

9781441211378

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

2 Mo

© 2003 by Michael Phillips

Published by Bethany House Publishers 11400 Hampshire Avenue South Bloomington, Minnesota 55438 www.bethanyhouse.com

Bethany House Publishers is a division of Baker Publishing Group, Grand Rapids, Michigan. www.bakerpublishinggroup.com

Ebook edition created 2010

Ebook corrections 04.15.2016 (VBN), 11.21.2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—for example, electronic, photocopy, recording—without the prior written permission of the publisher. The only exception is brief quotations in printed reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

ISBN 978-1-4412-1137-8

Uncle Remus stories are the creation of Joel Chandler Harris (1848–1908).

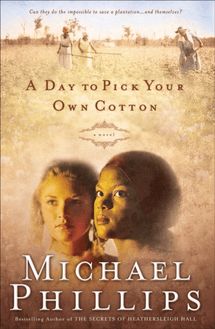

Cover photo of girls by David Bailey Cover photo of plantation by Paul Taylor, IndexStock Cover design by The DesignWorks Group, Kirk DouPonce

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Remembering

1. W INDS OF C HANGE

2. S PECIAL P LACE

3. A V ISIT TO T OWN

4. P UZZLING W ORDS

5. W AR C OMES

6. T WISTER

7. A V ISITOR

8. D ESERTION

9. H OMECOMING

10. T RAGEDY

11. M AYME

12. M ASSACRE

13. A WAY

14. F IRST D AY

15. W HAT N OW?

16. M OVIN’ O N

17. R OUTINE AND A N EW B ED

18. N EIGHBORLY C ALL

19. I NVESTIGATION

20. S PECIAL D AY

21. B OOKS , D OLLS, AND B EDTIME S TORIES

22. W ORKING AND L EARNING T OGETHER

23. K ATIE’S P OEMS

24. M RS . H AMMOND

25. T HE S ECRETARY A GAIN

26. T HE G OOD B OOK

27. R ETURN

28. A L OT OF G ROWING U P TO D O

29. M ESSAGE IN THE B IBLE

30. S ERIOUS T ALK

31. K ATIE’S S PECIAL P LACE

32. Q UESTIONS

33. U NEXPECTED V ISITORS

34. T AKING ON THE M OTLEY S TRANGERS

35. I M AKE A D ECISION

36. G OOD-BYE TO R OSEWOOD

37. N EW E MERGENCY

38. A NOTHER M EETING

39. T HREE G IRLS D OING W HAT W OMEN D O

40. A D IFFERENCE

41. T HE A RGUMENT

42. L EAVING A GAIN

43. T HE D ARING S CHEME

44. J UST M E AND G OD

45. M AKING P LANS

Epilogue

About the Author

Other Books by Michael Phillips

To Contact the Author

Back Cover

Katie and I’d been born in the same county only a year apart, but it might as well have been in different centuries on opposite sides of the world. . . .

Remembering . . .

I ’VE BEEN MAKING UP STORIES SINCE BEFORE I can remember.

As near as I can recollect, it started so as to keep my little brother from crying. If I could just get his attention for a minute or two on something besides the hunger in his stomach or wishing our mama was back in from the fields, he’d shush up and start paying attention. Then I’d have to think up something else mighty quick.

And something after that . . . and I’d string it all together with interesting expressions and in different voices so he’d keep looking at me with those big, wide eyes of his and keep listening and not take to crying again.

Before I knew it, I was spinning out tales that’d keep him quiet for hours. I had no idea what was going to come next but just made it up as I went along. Then the next day when he’d need more stories, I would string along some more where I’d left off.

Sometimes I’d look up, and there’d be our mama, finally home again and listening too, with a kind of peculiar look on her face to hear what I was telling the young’un, our little Samuel.

‘‘Where’d you hear dat story from, chil’?’’ she asked me once.

I said I didn’t hear it from anyplace. I’d just made it up.

‘‘What ’bout all them little sayin’s you add now an’ then?’’

I shrugged. I hadn’t really thought on it.

‘‘Where’d you learn dose?’’ she pressed.

‘‘No place, Mama,’’ I said.

‘‘But yo’re too young ter know sech things.’’

‘‘I can’t help it, Mama. They just come out when I’m tellin’ the story.’’

Then she said something I never forgot, and it’s helped me keep my head up through some hard times, and I’ve had a heap of them.

‘‘Well, chil’,’’ she said, ‘‘dis here’s a hard life we lead. We neber know what’s gwine happen ter any of us from day ter day. You ain’t da most fetchin’-lookin’ young’un I eber seen. But you got some unordinary smarts in dat brain of yors. So I reckon you’ll get along all right fine in dis ole worl’, whateber becomes of you.’’

She paused and smiled at me with that same funny kind of expression on her face. Now that the years have passed and I’m older, I realize it was a look that said how much she loved me. Then she passed the back of her rough black hand across my cheek and spoke again.

‘‘So you jes’ keep tellin’ yor stories,’’ she said, ‘‘an’ you pay ’tention to what’s in dat head of yors. ’Cause da good Lord’s giben you a gif ’ most folks ain’t got.’’

I nodded, but I only half understood what she was trying to say. It takes a lot of years before young folks can really catch on to what their mamas and papas tell them when they’re young.

At first, like I said, I just told stories to my little brother Samuel, and I never had much thought about writing anything down. I loved to listen to the yarns the old slaves would spin around our nightly fires, and I’d tell Sammy those stories too, sometimes adding stuff of my own to them. I especially liked the ones about Mr. Rabbit and Mr. Fox. They were my favorites of the old tales.

I didn’t even know how to write when I listened to the first stories and started passing them on to Sammy. But by the time I was ten or so, Mama had taught me to write.

It was uncommon the way she knew how to read and write. Not many slaves had schooling. In fact, lots of their owners got real nervous about slaves learning things like that. But she’d been born to a house slave, and when she was little she listened when the master’s children were getting their lessons. She sure didn’t get her hands on books too often, but when she did, she ate up the words like she was starving for them.

Anyway, Mama started to bring me every scrap of paper she could find, most of the time taking wrappings from the trash heap and cutting them all down to the same size. Then I started to write things down, kind of like a diary, I reckon. And ideas for made-up stories too. Keeping my diary on those scraps of paper we collected, just like Mama said, helped me through some hard times, and helped me remember things it was important to remember.

So that’s how my storytelling all got started. Right now I’m holding a special leather-bound diary in my hands that’s nearly as old as I am. How I came to have such a special keepsake is something that’s an important part of what I’ll be telling you. But for now you should know I’ve written down things in it from some of those long-ago pieces of paper, and it sure is going to help me remember important events of my life that I want to tell you about.

I’ve got something else in front of me as I write. It’s small and blue and white and gold, but I can’t describe it more than that without telling how it came to be, and I’d be getting ahead of myself to do that just yet. But these two things along with my mama’s Bible, are all I have left from those days way back then. Putting all those memories into words is going to take every ounce of energy and clear thinking I can muster. So I’ve got the diary and my memory, such as it is, to help me piece together the events as well as the thoughts, and especially the feelings, that shaped my life and Katie’s.

Just hang in there with me for a minute, and I’ll explain who Katie was.

The particular time I’ve been talking about, I must have been maybe six or seven, and of course that was before I was writing anything down. My brother was born about three years after me, so that would have made him three or four, which is probably the age when an older sister starts telling a young’un stories.

If that’s when I told my first story, that would be more years ago than you likely can imagine, especially some of you who think even thirty or forty is old. I’m not planning to tell you exactly how old I am, but the fact is, I’ve done a lot of living since my earliest storytelling days.

I remember the first time I ever saw an automobile, and, land’s sakes, I was petrified and fascinated all at the same time. When the new century arrived, I was still living in Shenandoah County, and by then it was one thing after another—telephones and cameras and electricity and whatnot—that were all announcing themselves faster than I could catch my breath.

So it’s probably not hard to see why I have a difficult time remembering exact dates of things. And if you asked me about any of those stories that I told Samuel, I’d answer that I could no more recall them than I can tell you what happened on the day I was born.

You are probably wondering what has made me want to go back and relive that life back in Shenandoah County, North Carolina. Especially when some of those days were pretty awful. Well, something has happened that will explain why I’m digging around in my past. Mine and Katie’s.

But, anyway, I can’t quite recollect exactly how all those stories for my little brother got into my head—which ones I heard from other black storytellers and which ones I made up. I think some of them got mixed up with the old slave songs too, because we all loved to sing. And sometimes when I sing those songs now, I seem to be able to recollect things right clearly. But gradually those early years of my life are slowly fading away, kind of like I’m looking off in the distance on a cold, sunny winter morning, when the fog gets thicker and thicker until you can’t make out anything at all. That’s how it is when I try to think of Samuel now.

Memory’s a funny thing. Some bits of it come back easier than others. Sometimes I can remember something that happened when I was seven better than what happened yesterday.

But what I remember most clearly starts when I was fifteen.

That’s how old I was when I first laid eyes on Katie.

I can’t help thinking