A Certain Amount of Madness , livre ebook

401

pages

English

Ebooks

2018

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Découvre YouScribe et accède à tout notre catalogue !

Découvre YouScribe et accède à tout notre catalogue !

401

pages

English

Ebooks

2018

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Publié par

Date de parution

20 mars 2018

Nombre de lectures

2

EAN13

9781786802248

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

5 Mo

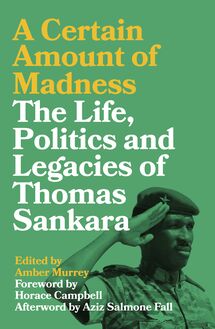

Thomas Sankara was one of Africa's most important anti-imperialist leaders of the late 20th Century. His declaration that fundamental socio-political change would require a 'certain amount of madness' drove the Burkinabe Revolution and resurfaced in the country's popular uprising in 2014.

This book looks at Sankara's political philosophies and legacies and their relevance today. Analyses of his synthesis of Pan-Africanism and humanist Marxist politics, as well as his approach to gender, development, ecology and decolonisation offer new insights to Sankarist political philosophies. Critical evaluations of the limitations of the revolution examine his relationship with labour unions and other aspects of his leadership style. His legacy is revealed by looking at contemporary activists, artists and politicians who draw inspiration from Sankarist thought in social movement struggles today, from South Africa to Burkina Faso.

In the 30th anniversary of his assassination, this book illustrates how Sankara's political praxis continues to provide lessons and hope for decolonisation struggles today.

Foreword by Horace G. Campbell

Acknowledgements

Introduction by Amber Murrey

Part I: Life and Revolution

1. Military Coup, Popular Revolution or Militarised Revolution?: Contextualising the Revolutionary Ideological Courses of Thomas Sankara and the National Council of the Revolution - De-Valera N.Y.M. Botchway and Moussa Traore

2. The Perils of Non-Alignment: Thomas Sankara and the Cold War - Brian Peterson

3. Thomas Sankara and the Elusive Revolution - Leo Zeilig

4. When Visions Collide: Thomas Sankara, Trade Unions and the Revolution in Burkina Faso, 1983-1987 - Craig Phelan

5. Africa’s Sankara: On Pan-African Leadership - Amber Murrey

6. Who Killed Thomas Sankara? - Bruno Jaffré

7. ‘Incentivized’ Self-Adjustment: Reclaiming Sankara’s Revolutionary Austerity from Corporate Geographies of Neoliberal Erasure - Nicholas A. Jackson

Part II: Political Philosophies

8. Madmen, Thomas Sankara and Decoloniality in Africa - Ama Biney

9. With the People: Sankara’s Humanist Marxism - Ernest Harsch

10. Thomas Sankara & Tajudeen Abdul-Raheem: The Untimely Deaths of Two New Generation African Visionaries - Patricia Daley

11. Women's Freedoms are the Heartbeat of Africa's Future: A Sankarian Imperative - Patricia McFadden

12. Re-Reading Sankara’s Philosophy for a Praxeology of Debt in Contemporary Times - Sakue-C. Yimovie

13. Sankara’s Political Ideas and Pan-African Solidarity: A Perspective for Africa’s Development? - Felix Kumah-Abiwu and Olusoji Alani Odeyemi

14. ‘Revolution and Women’s Liberation Go Together’: Thomas Sankara, Gender and the Burkina Faso Revolution - Namakula E. Mayanja

Part III: Legacies

15. Balai Citoyen: A New Praxis of Citizen Fight with Sankarist Inspirations - Zakaria Soré

16. La Santé Avant Tout: Health Before Everything - T. D. Harper-Shipman

17. Social Movement Struggles and Political Transition in Burkina Faso - Bettina Engles

18. To Decolonize the World: Thomas Sankara and the ‘Last Colony’ in Africa - Patrick Delices

19. ‘Daring to Invent the Future’: Sankara’s Legacy and Contemporary Activism in South Africa - Levi Kabwato and Sarah Chiumbu

Part IV: Contestations and Homages

20. The Academy as Contested Space: Disappearing Sankara from the ‘Acceptable Avant-Garde’ - Nicholas A. Jackson

21. Art and the Construction of a ‘Sankara Myth’: A Hero Trend in Contemporary Burkinabè Urban & Revolutionary Propaganda Art - Sophie Bodénès Cohen

22. Slanted Photography: Reflections on Sankara and My Peace Corps Experience in Burkina Faso - Celestina Agyekum

23. ‘We Are the Children of Sankara’: Memories as Weapons during the Burkinabe Uprisings of 2014 and 2015 - Fiona Dragstra

Afterword by Aziz Salmone Fall

Notes on Contributors

Index

Publié par

Date de parution

20 mars 2018

EAN13

9781786802248

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

5 Mo

A Certain Amount of MadnessBlack Critique

Series editor: Anthony Bogues

We live in a troubled world. The rise of authoritarianism marks the dominant

current political order. The end of colonial empires did not inaugurate a more

humane world; rather, the old order reasserted itself.

In opposition, throughout the twentieth century and until today, anti-racist,

radical decolonization struggles attempted to create new forms of thought.

Figures from Ida B. Wells to W.E.B. Du Bois and Steve Biko, from Claudia Jones

to Walter Rodney and Amílcar Cabral produced work which drew from the

historical experiences of Africa and the African diaspora. They drew inspiration

from the Haitian revolution, radical black abolitionist thought and practice,

and other currents that marked the contours of a black radical intellectual and

political tradition.

The Black Critique series operates squarely within this tradition of ideas and

political struggles. It includes books which foreground this rich and complex

history. At a time when there is a deep desire for change, black radicalism is

one of the most underexplored traditions that can drive emancipatory change

today. This series highlights these critical ideas from anywhere in the black

world, creating a new history of radical thought for our times.

Also available:

Red International and Black Caribbean:

Communists in New York City, Mexico and the West Indies, 1919–1939

Margaret StevensA Certain Amount

of Madness

The Life, Politics and Legacies of

Thomas Sankara

Edited by Amber Murrey

Foreword by Horace Campbell

Afterword by Aziz Salmone FallFirst published 2018 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright © Amber Murrey 2018

The right of the individual contributors to be identified as

the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3758 6 Hardback978 0 7453 3757 9 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7868 0224 8 PDF eBook978 1 7868 0226 2 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0225 5 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully

managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing

processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Swales & Willis

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

Half of all author proceeds for this book are donated to the June Givanni Pan-African

Cinema Archive (www.junegivannifilmarchive.com). This is the largest archive of

Pan-African filmmaking in Europe, operating to promote Pan-African art and

philosophy to a wide audience, supporting Black artists in a colonial matrix that

otherwise marginalizes their perspectives and cultivating an appreciation for Black life

and art – all causes that were foundational to Sankara’s radical Pan-African vision.For Ndewa Jean (1948–1990)

and all the others who wept

on 15 October 1987Contents

Foreword by Horace G. Campbell xi

Acknowledgements xvii

Introduction 1

Amber Murrey

Part I Life and Revolution 19

1 Military Coup, Popular Revolution or Militarised Revolution?:

Contextualising the Revolutionary Ideological Courses of

Thomas Sankara and the National Council of the Revolution 21

De-Valera N. Y. M. Botchway and Moussa Traore

2 The Perils of Non-Alignment: Thomas Sankara and the Cold War 36

Brian Peterson

3 Thomas Sankara and the Elusive Revolution 51

Leo Zeilig

4 When Visions Collide: Thomas Sankara, Trade Unions and the

Revolution in Burkina Faso, 1983–1987 62

Craig Phelan

5 Africa’s Sankara: On Pan-African Leadership 75

Amber Murrey

6 Who Killed Thomas Sankara? 96

Bruno Jaffré

7 ‘Incentivized’ Self-Adjustment: Reclaiming Sankara’s Revolutionary

Austerity from Corporate Geographies of Neoliberal Erasure 113

Nicholas A. Jackson

Part II Political Philosophies 125

8 Madmen, Thomas Sankara and Decoloniality in Africa 127

Ama Bineyviii | Contents

9 With the People: Sankara’s Humanist Marxism 147

Ernest Harsch

10 Thomas Sankara and Tajudeen Abdul-Raheem: The Untimely

Deaths of Two New Generation African Visionaries 159

Patricia Daley

11 Women’s Freedoms are the Heartbeat of Africa's Future: A Sankarian

Imperative 170

Patricia McFadden

12 Re-Reading Sankara’s Philosophy for a Praxeology of Debt in

Contemporary Times 180

Sakue-C. Yimovie

13 Sankara’s Political Ideas and Pan-African Solidarity: A Perspective

for Africa’s Development? 194

Felix Kumah-Abiwu and Olusoji Alani Odeyemi

14 ‘Revolution and Women’s Liberation Go Together’:

Thomas Sankara, Gender and the Burkina Faso Revolution 209

Namakula E. Mayanja

Part III Legacies 223

15 Balai Citoyen: A New Praxis of Citizen Fight with

Sankarist Inspirations 225

Zakaria Soré

16 La Santé Avant Tout: Health before Everything 241

T. D. Harper-Shipman

17 Social Movement Struggles and Political Transition in Burkina Faso 255

Bettina Engels

18 To Decolonize the World: Thomas Sankara and the

‘Last Colony’ in Africa 269

Patrick Delices

19 ‘Daring to Invent the Future’: Sankara’s Legacy and

Contemporary Activism in South Africa 286

Levi Kabwato and Sarah Chiumbu

Part IV Contestations and Homages 305

20 The Academy as Contested Space: Disappearing Sankara from the

‘Acceptable Avant-Garde’ 307

Nicholas A. JacksonContents | ix

21 Art and the Construction of a ‘Sankara Myth’: A Hero Trend in

Contemporary Burkinabè Urban and Revolutionary Propaganda Art 313

Sophie Bodénès Cohen

22 Slanted Photography: Reflections on Sankara and My Peace Corps

Experience in Burkina Faso 328

Celestina Agyekum

23 ‘We Are the Children of Sankara’: Memories as Weapons during the

Burkinabè Uprisings of 2014 and 2015 335

Fiona Dragstra

Afterword 349

Aziz Salmone Fall

Notes on Contributors 361

Index 367Foreword

The Life and Legacy of Thomas Sankara

Horace G. Campbell

Thomas Sankara was born in Burkina Faso in 1949, the same year that the

Chinese Revolution succeeded in laying the foundations for a transition to

socialism. This revolution had succeeded after years of war, sacrifice and

ideological struggle. Sankara was killed in 1987, the year of the decisive military

change to defeat apartheid militarism in Africa. In the 37 years while Sankara

traversed the earth, he was shaped by the political, social and ideological

struggles in the anti-imperialist world. Sankara helped to assert the claim of

African peoples to be a part of those defining the future of humanity. In his

adult years, Sankara served as a soldier in the armed forces of Burkina Faso.

This was a branch of the imperial military chain to control the labour power

of the producing classes in Africa. He made a decisive break with this tradition.

Burkina Faso was previously called Upper Volta, one of the regions of French

colonial plunder and exploitation in Africa. Sankara had been groomed to

serve these interests but he wanted to be a decent human being in a society of

upright human beings. Hence in the period of his short leadership of Burkina

Faso, 1983-1987, he changed the name and orientation of the society to signal a

Pan-African assertion of dignity and self-confidence. These two aspects of

selfdetermination have now been inscribed within the project for the unification

and emancipation of a socialist Africa. Sankara’s life and work as a soldier left

many lessons for the African revolutionaries of today, whose task it is to speed

the break from imperial domination. The 23 chapters of this book on Sankara

remind the younger generation of what a life of dignity can do for peoples

everywhere.

birth in the shadow of revolutionary changes

Thomas Sankara was born in a territory that had been exploited by France in

its bid to represent itself as a major force in world politics. Both Britain and

France had been diminished by the Second Imperialist war and wars of national xii | Foreword

liberation from China and Vietnam to Malaysia and Egypt had weakened both

colonial powers. The United States had emerged out of World War II as the

dominant imperial force and had created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization

to defend global capital. France and Britain had mobilised colonial troops to

maintain its place at the international table of Global Capital. Colonial armies

were deployed in Vietnam and the marginalized elements of colonial societies

were recruited as foot soldiers for the dying colonial enterprise. Hence in places

such as the Central African Republic and Uganda, soldiers were recruited to

fight to save French and British capitalism. Jean Bedel Bokasa of the Central

African Republic and Idi Amin of Uganda were two archetype colonial soldiers

who fought against freedom fighters in Indo China and in Kenya. It was this

tradition of fighting against the forces of self-determination that was drilled

into soldiers all across Africa after World War II. Those soldiers who supported

the independence struggles, such as Dedan Kimathi of Kenya, had lent their

military skills and training to the task of freeing Africa.

By the time Thomas Sankara was ten years old, the Cuban Revolution had

sent a message that size was not a barrier in the fight for freedom. The emergence

of the military and political ideas of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara had become

a new source of inspiration for youths all across the anti-imperialist world. It

was this world into which Thomas Sankara grew. Upper Volta, as his home

society was called, was a reservoir of workers and soldiers from the French

imperial system. The super exploitation of the working poor and farmers in

the society was amplified by a system of migration where the poor of worked

as cheap, bonded labor in the farms of Ghana and Ivory Coast. Hence the class

character of Upper Volta was shaped by the dominance of French capital, with

French com