The Gothic Ideology , livre ebook

375

pages

English

Ebooks

2014

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

Découvre YouScribe en t'inscrivant gratuitement

375

pages

English

Ebooks

2014

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Publié par

Date de parution

15 mai 2014

Nombre de lectures

1

EAN13

9781783160495

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

9 Mo

Table of Contents List of Figures Acknowledgments Introduction Chapter One: Anti-Catholicism and the Gothic Ideology: Interlocking Discourse Networks Chapter Two: The Construction of the Gothic Nun: Fantasy and the Religious Imaginary Chapter Three: The Spectre of Theocracy: Mysterious Monks and "Priestcraft" Chapter Four: The Foreign Threat: Inquisitions, autos-da-fe, and Bloody Tribunals Chapter Five: Ruined Abbeys: Justifying Stolen Property and the Crusade against Superstition EPILOGUE: Penny Dreadfuls and the (Almost) Last Gasp of the Gothic

Publié par

Date de parution

15 mai 2014

Nombre de lectures

1

EAN13

9781783160495

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

9 Mo

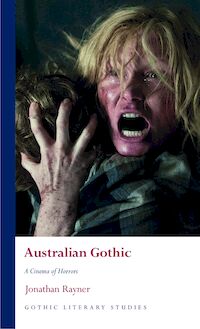

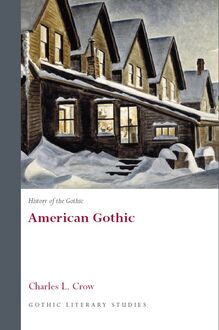

THE GOTHIC IDEOLOGYSERIES PREFACE

Gothic Literary Studies is dedicated to publishing

groundbreaking scholarship on Gothic in literature and film. The Gothic,

which has been subjected to a variety of critical and theoretical

approaches, is a form which plays an important role in our

understanding of literary, intellectual and cultural histories. The

series seeks to promote challenging and innovative approaches

to Gothic which question any aspect of the Gothic tradition or

perceived critical orthodoxy. Volumes in the series explore how

issues such as gender, religion, nation and sexuality have shaped

our view of the Gothic tradition. Both academically rigorous

and informed by the latest developments in critical theory, the

series provides an important focus for scholarly developments

in Gothic studies, literary studies, cultural studies and critical

theory. The series will be of interest to students of all levels and

to scholars and teachers of the Gothic and literary and cultural

histories.

SERIES EDITORS

Andrew Smith, University of Sheffield

Benjamin F. Fisher, University of Mississippi

EDITORIAL BOARD

Kent Ljungquist, Worcester Polytechnic Institute Massachusetts

Richard Fusco, St. Joseph’s University, Philadelphia

David Punter, University of Bristol

Chris Baldick, University of London

Angela Wright, University of Sheffield

Jerrold E. Hogle, University of ArizonaThe Gothic Ideology

Religious Hysteria and Anti-Catholicism

in British Popular Fiction 1780–1880

Diane Long Hoeveler

UNIVERSITY OF WALES PRESS

CARDIFF

2014© Diane Long Hoeveler 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without clearance from the University of Wales Press, 10 Columbus

Walk, Brigantine Place, Cardiff, CF10 4UP.

www.uwp.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978–1–7831–6048–8

e-ISBN 978–1–7831–60495

The right of Diane Long Hoeveler to be identified as author of this

work has been asserted by her in accordance with sections 77 and 79

of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Typeset by Prepress Projects Ltd, Perth, UK

Printed in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, WiltshireCONTENTS

List of Illustrations vii

Acknowledgements ix

Introduction 1

1 Anti-Catholicism and the Gothic Ideology:

Interlocking Discourse Networks 15

2 The Construction of the Gothic Nun: Fantasies and

the Religious Imaginary 51

3 The Spectre of Theocracy: Mysterious Monks and

‘Priestcraft’ 98

4 The Foreign Threat: Inquisitions, Autos-da-Fé and

Bloody Tribunals 147

5 Ruined Abbeys: Justifying Stolen Property and the

Crusade against Superstition 197

Epilogue: The Penny Dreadful and the (Almost) Last

Gasp of the Gothic Ideology 247

Notes 265

Bibliography 293

Appendix: Anti-Catholic/Gothic Titles 321

Index 343LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Figure 1.1: Gissey de Bordelet, Histoire du Père Jean

Baptiste Girard Jésuite, et de la Delle Marie-Catherine

Cadière, divisee en 32 planches 34

Figure 2.1: Chapbook version of Eliza, or the

Unhappy Nun 67

Figure 2.2: Frontispiece to The Nun; or, Memoirs of

Angelique; An Interesting Tale 73

Figure 2.3: Frontispiece to The Legends of a Nunnery 87

Figure 3.1: FFather Innocent 112

Figure 4.1: Frontispiece to Brompton Revelations 151

Figure 4.2: Climactic scene from G. W. M. Reynolds’s

The Bronze Statue, or The Virgin’s Kiss 154

Figure E.1: Mysteries of a London Convent 248

Figure E.2: Poster advertising the production of Le

Diable au Couvent by Eugène Hugot 261ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Writing a book is often a lonely and haphazard journey,

frequently full of potholes and dead ends. The composition

of this book, however, was a pleasure, filled with charming

vistas, intriguing interludes, and challenging but exhilarating

jaunts into new territory. It is my pleasure here to thank the

people who made this trip so enjoyable: Marquette University’s

Committee on Research awarded me a three-year Way-Klingler

Humanities Fellowship to travel to archives and libraries in

America and Europe in order to gather the primary texts used

here, and for that support I am immensely grateful. In Paris I was

hosted by Pascale Sardin at the Institut du Monde Anglophone,

Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3, and I would like to

thank the audience there for asking me such probing questions

during my visit; in Germany I was hosted by Norbert Besch,

the man with a treasure trove of Gothic arcana at his fingertips;

and in Toulouse I was hosted by Maurice Lévy, the late great

French Gothicist who allowed me to digitize his French Gothic

collection before it was shipped to the University of Virginia in

2012. In England, I was hosted by Chloe Chard and twice by

Nora and Keith Crook, and I will always be grateful for their

hospitality and kindness to me.

The scholarly Gothic/Romantic community has embraced

my work and made me feel particularly supported. Special

thanks go to Robert Miles, David Punter, Anne Williams,

Steve Bruhm, Bill Hughes, Andrew Smith, Avril Horner, Sue

Zlosnik, Dale Townshend, Angela Wright and Tina Morin.

Colleagues who have read my work or have always been

generous with their time are Stephen Behrendt, Marshall Brown,

Fred Burwick, Benjamin Colbert, David Collings, Jeff Cass, The Gothic Ideology

Jeff Cox, Gary Dyer, Nancy Goslee, Jonathan Gross, Nicholas

Halmi, Regina Hewitt, Jeff Kahan, Gary Kelly, John Mahoney,

Victoria Nelson, Richard Sha, Douglas Thomson, Jack Voller

and Judith Wilt. I am particularly grateful to David Salter and

Marie Léger-St-Jean for reading drafts of this work at an early

stage and offering helpful advice and encouragement. Several

sections of this book were originally presented at conferences

held by the British Association of Romantic Studies, the

International Gothic Association, the International Conference

on Romanticism, the Humanities Center at DePaul University,

and the North American Society for the Study of Romanticism.

Scholars and librarians who have helped me track down

images and references and have gone above and beyond in

answering my frequent queries are John Adcock, Elizabeth James,

Louis James, Andrea Lloyd, Michael Ferber, Michael Gavin,

Justin Gilbert, Steve Holland, Denis Paz, Elizabeth Denlinger,

Patrick Scott, John Selby, Nancy F. Sweet and Stephen Karian.

My research assistants at Marquette – Brian Kenna, Abby Vande

Walle, Camilia Cenek and Robin Graham – did the hard work

of converting digital material to Word files for my use. Rose

Fortier transferred most of the chapbooks discussed in this book

to the online site, ‘The Gothic Archive’. I am immensely grateful

for her technical savvy. Joan Sommer at Marquette University’s

office of interlibrary loan handled more requests than I am sure

she cares to remember, and I would like to thank the librarians

and curators who were extraordinarily patient when I was such

a persistent presence at a variety of libraries: the British Library,

Cambridge University Library, the Bodleian Library, Oxford,

the Sadleir–Black collection at the University of Virginia Library,

the Pforzheimer Collection, the New York Public Library, the

Library of Congress, the Bibliotèque-Nationale-Richelieu and

Tolbiac, and the Bibliothèque-musée de l’Opéra-Paris.

I am also indebted to the editors of Religion in the Age of

Enlightenment and European Romantic Review for permission to

republish materials originally printed in different versions in

those venues. At the University of Wales Press, I would like to

acknowledge the skilful editorial work of Sarah Lewis and Sian

Chapman. Thanks also to Andrew Davidson and Claire Rose

xAcknowledgements

at Prepress Projects. I am also immensely grateful to Professor

Jerry Hogle of the University of Arizona, who served as the

press’s external reader and provided astute and very helpful

critiques during the publication process. At Marquette, I am

grateful for the support of my dean, Fr Philip Rossi, SJ. And, as

always, it is a pleasure to thank my beloved and loving family,

David, John and Emily Hoeveler.

xiK

Introduction

Falsis terroribus Implet [Torture my breast with fictions]

Epistles (Horace, 1749: II. 398)

Getting its history wrong is part of being a nation.

What Is a Nation? (Renan, 1990: 12)

The cover of this book, an illustration from Purkess’s 1848

penny dreadful adaptation of Matthew Lewis’s vehemently

anti-Catholic novel The Monk (1796), depicts very clearly the

hysterical energy that was brought to the issue of religion in what

1was supposedly a progressive era. Representing the climactic

moment in the text when the Franciscan monk Ambrosio

seizes his sister Antonia by the hair just after raping her in the

catacombs beneath his Madrid monastery, the illustration spoke

to the general public’s pervasive fears about the presence of an

increasing number of Catholic clergy in a Britain that was by this

time thoroughly invested in a form of nationalistic Protestantism.

This scene of a sadistic monk raping, torturing and murdering

a young innocent woman (and in this case, unbeknownst

to him, his long-lost sister) was continually reprinted in the

penny press throughout the century, while depictions of The

Monk’s perverse and violent attacks on his mother and sister

were persistently popular tropes in Gothic texts, so frequently

repeated that one marvels at how the populace could not have The Gothic Ideology

been quickly sated with their depiction. However, quickly sated

they do not seem to have been. Variations on this representation

have continued to appear in hundreds of literary texts for over

200 years, seemingly in direct contradiction to claims recently

made by Franco Moretti (2009). Using more than 7,000 novels

from several different countries published over a 160-year

per