Cultivating the Heart , livre ebook

177

pages

English

Ebooks

2015

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Découvre YouScribe et accède à tout notre catalogue !

Découvre YouScribe et accède à tout notre catalogue !

177

pages

English

Ebooks

2015

Obtenez un accès à la bibliothèque pour le consulter en ligne En savoir plus

Publié par

Date de parution

15 juin 2015

Nombre de lectures

3

EAN13

9781783162659

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

3 Mo

Cultivating the Heart examines the nurturance of feeling – especially the intertwined affective stirrings of compassion, love, and sorrow – in a range of religious texts from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. These texts encourage, stimulate, define and attempt to express the ‘cultivation of hearts’, an image inspired by Part VII of Ancrene Wisse, whereby readers and audiences of the texts nurture a range of sophisticated ‘affective literacies’. In addition to extensive analysis of English, Latin and Anglo-Norman texts, this book makes substantial reference to the affective strategies of wall paintings in parish churches, demonstrating how the affective strategies of wall paintings cannot be perceived as inferior to or irreconcilable with the affective import of textual media.

Introduction

Chapter 1: Upon a Spiritual Cross: Feeling in the Lambeth and Trinity Homilies

Chapter 2: The Gnawed Hand: Presence and Absence of Feeling in the Early South English Legendaries

Chapter 3: Co-feeling: Compassion in Ancrene Wisse and the Wooing Group

Chapter 4: Call Me Bitter: Feeling and Sensing in Passion Lyrics

Conclusion

Publié par

Date de parution

15 juin 2015

EAN13

9781783162659

Langue

English

Poids de l'ouvrage

3 Mo

RELIGION AND CULTURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

Cultivating the HeartSeries Editors

Denis Renevey (Université de Lausanne)

Diane Watt (University of Surrey)

Editorial Board

Miri Rubin (Queen Mary University of London)

Jean- Claude Schmitt (École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Paris)

Fiona Somerset (Duke University)

Christiania Whitehead (University of Warwick)RELIGION AND CULTURE IN THE MIDDLE AGES

Cultivating the Heart

FEELING AND EMOTION IN TWELFTH- AND

THIRTEENTH-CENTURY RELIGIOUS TEXTS

A. S. LAZIKANI

UNIVERSITY OF WALES PRESS

2015$

D

Z

E

© A. S. Lazikani, 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form

(including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether

or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the

written permission of the copyright owner. Applications for the copyright owner’s

written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the

University of Wales Press, 10 Columbus Walk, Brigantine Place, Cardiff CF10 4UP.

www.uwp.co.uk

British Library CIP Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-78316-261-1 (hardback)

978-1-78316-264-2 (paperback)

e- ISBN 978-1-78316-265-9

asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents

Act 1988.

Typeset by Eira Fenn Gaunt, Pentyrch, Cardiff

Printed by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham, Wiltshire

EHHQ KDV RUN WKLV RI RI ULJKW 7KH DXWKRU VLGHQWL¿HG H WR/D]LNDQL6DUPDGD \RXVKCONTENTS

Series Editors’ Preface vii

List of Illustrations ix

Acknowledgements xi

List of Abbreviations xiii

Note on Editions and Translations xv

Introduction: Feeling in the High Middle Ages 1

1 Upon a Spiritual Cross: Feeling in the Lambeth and Trinity Homilies 25

2 The Gnawed Hand: Presence and Absence of Feeling in the Early South

English Legendaries 49

3 Co-feeling: Compassion in Ancrene Wisse and the Wooing Group 71

4 Call Me Bitter: Feeling and Sensing in Passion Lyrics 93

Conclusion 121

Notes 125

Select Bibliography 149

Index 153 UROHV

V

Z

E

RZQHUV

H

E\

P

W

Q

RI

:

UHDGHUV

KH

W

S

WKDQ

IXUWKHU

W

W

RGHUQ

L

FLSOLQHV

W

D

ERRNV

W

F

L

W

W

DQG

V

DXWKRUV

Z

D

Z

ZRPHQ

D

OD\HG

H

D

U

WKH

Z

H[SORUH

G

R

Z

ZDQW

D

R

W

L

I

G

G

F

SERIES EDITORS’ PREFACE

Religion and Culture in the Middle Ages aims to explore the interface between medieval

religion and culture, with as broad an understanding of those terms as possible. It puts

WR KH IRUHIURQW WXGLHV KLFK QJDJH LWK RUNV KDW VLJQL¿FDQ WO\ RQWULEXWHG R WKH

shaping of medieval culture. However, it also gives attention to studies dealing with

KD FXOWXUH PHGLHYDO RI VSHFWV KLJKOLJKW DQG UHÀHFW KDW ZRUNV Q HJOHFWHG HHQ KDYH W

the past by scholars of the medieval disciplines. For example, devotional works and the

practice they infer illuminate our understanding of the medieval subject and its culture

in remarkable ways, while studies of the material space designed and inhabited by

medieval subjects yield new evidence on the period and the people who shaped it and

DOV ZH FXOWXUH DQG UHOLJLRQ RI ¿HOG JHU ODU WKH ,Q LW Q OLYHG

WKHP GH¿QLQJ WKHUHE\

PRUH SUHFLVHO\ V DFWRUV Q WKH FXOWXUDO ¿HOG 7KH VHULHV V D ZKROH LQYHVWLJDWHV WKH

European Middle Ages, from c.500 to c.1500. Our aim is to explore medieval religion

and culture with the tools belonging to such disciplines as, among others, art history,

philosophy, theology, history, musicology, the history of medicine, and literature. In

particular, we would like to promote interdisciplinary studies, as we believe strongly

that our modern understanding of the term applies fascinatingly well to a cultural period

LV LWV RI FDWHJRUL]DWLRQ DQG RQ¿QHPHQW WLJKW OHVV D E\ PDUNHG

period. However, our only criterion is academic excellence, with the belief that the use

of a large diversity of critical tools and theoretical approaches enables a deeper

XQGHUVWDQGLQJ RI PHGLHYDO FXOWXUH DQW WKH VHULHV R UHÀHFW KLV GLYHUVLW\ DV H

believe that, as a collection of outstanding contributions, it offers a more subtle

representation of a period that is marked by paradoxes and contradictions and which

QHFHVVDULO\ HÀHFWV LYHUVLW\ QG HUHQFH GLI KRZHYHU LI¿FXOW LW PD\ VRPHWLPHV KDYH

proved for medieval culture to accept these notions.ILLUSTRATIONS

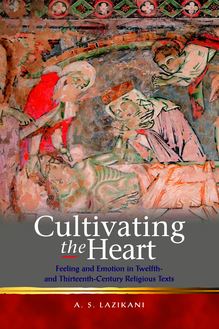

1 Passion Cycle on East Wall in St Mary’s Church, Brook, Kent (c.1260–80)

2 Passion sequence on South Wall in St Michael’s Church, Great Tew, Oxfordshire

(c.1290)

3 Wall of the nave of St Mary’s Church, West

Chiltington, Sussex (c.1250–75)

4 Detail of the Passion sequence in St Michael’s Church, Great Tew, Oxfordshire

(c.1290): ‘Noli me tangere’

All photographs are the author’s own. The approximate dates follow those given by

Anne Marshall in her ‘Painted Church’ project: <www.paintedchurch.org/> (accessed

June 2013).K

H

V

F

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to many eminent scholars and editors for their generous interest in

and feedback on this book as it has developed.

Most of all, I am very grateful to Dr Annie Sutherland for investing a great deal of her

time reading through my work and offering so much invaluable feedback, both as my

doctoral supervisor and in subsequent years. No student could have had a more caring

or inspiring supervisor.

Professor Vincent Gillespie and Professor Elizabeth Robertson also invested much of

their time as my doctoral examiners reading and correcting material that is now in this

book. I very much appreciate the wealth of feedback they have given me, and all their

kindness and encouragement both as my examiners and in subsequent years.

I am grateful to Professor Denis Renevey for his generous interest in this project and

for all his many stimulating suggestions, and to Dr Helen Barr for her supportive and

thoughtful comments on my work. Professor Bella Millett has taken the time to kindly

answer my many queries on homilies, and I thank also the anonymous reader of my

manuscript at the University of Wales Press for her valuable suggestions.

Dr Liz Herbert McAvoy and Dr Catherine Innes-Parker have, as always, shown me

great kindness, and Dr Alexandra Da Costa and Dr Aditi Nafde have been so encouraging.

I would also like to thank Dr Tony Hunt and Dr Jane Bliss for their very useful input on

Anglo-Norman texts.

In its earlier stages as a doctoral thesis, this project was funded by the Arts and

Humanities Research Council, and I am grateful to the AHRC for making this initial

research possible.

Thank you very much to Bertie and Bissan for advice about photographing church

wall paintings. I am so grateful to Maria for reading over parts of this book carefully, and

for all her warm encouragement over the past years. And thank you so much to Sabina

for all her support and friendship through this project’s development.

This book is dedicated to the memory of my mother, Amal, and to my father, Muhydin

YHU EH XI¿FLHQW ± IRU HYHU\WKLQJ WKH\ DYH GRQH DQG IRU ZKLFK QR ZRUGV RXOG

ABBREVIATIONS

AASS Acta Sanctorum quotquot tot orbe coluntur, vel à Catholicis

Scriptoribus celebratur, ed. Jean Bolland et al., 68 vols

(Brussels: Alphonsum Greise, 1863–1940)

EETS Early English Text Society (1864–)

O. S. Original Series (1864–)

E. S. Extra Series (1867–1920)

S. S. Supplementary Series (1970–)

MED Middle English Dictionary, ed. by Hans Kurath and S. M. Kuhn

(Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; London: Oxford

University Press, 1952–)

Online version (Michigan, 18 December 2001): <http://quod.lib.umich.

edu/m/med/>

PL Patrologiae cursus completus: series Latina, ed. by J. P. Migne,

221 vols (Paris: Migne, 1844–55 and 1862–5)

SEL South English Legendaries

NOTE ON EDITIONS AND TRANSLATIONS

Biblical References

Due to considerations of space, biblical references in most cases are to the

DouayRheims translation, and not to the original Latin Vulgate (The Holy Bible, Douay

Version: Translated from the Latin Vulgate (Douay, AD 1609: Rheims, AD 1582).

London: Catholic Truth Society, 1956).

Editions of Middle English

All quotations are taken from the following editions:

I The Lambeth and Trinity Homilies

Lambeth homilies:

Old English Homilies, First Series, ed. Richard Morris, EETS O. S. 29, 34 (London,

1867–8).

Trinity homilies:, Second Series, ed. Richard Morris, EETS O. S. 53 (London,

1873).

Punctuation has been modernized.

II South English Legendaries

The Early South-English Legendary, or, Lives of Saints, ed. Carl Horstmann, EETS O. S.

87 (London, 1887).

III Ancrene Wisse and the Wooing Group

Ancrene Wisse: A Corrected Edition of the Text in Cambridge, Corpus Christi College,

MS 402 with Variants from Other Manuscripts, ed. Bella Millett, 2 vols, EETS O. S. 325

and 326 (Oxford, 2005–6).

Þe Wohunge of ure Lauerd, etc., ed. W. Meredith Thompson, EETS O. S. 241 (London,

1958).

Given the heavily diplomatic nature of Thompson’s edition, the texts have been

re-edited from the manuscripts, but page numbers to Thompson’s edition are given for

the reader’s convenience. Abbreviations (with the exception of the Tironian nota) are xvi NOTE ON EDITIONS AND TRANSLATIONS

expanded, word-spacing is modernized, ‘wynn’ is rendered ‘w’, and interlinear or

marginal insertions in the manuscripts are also made silently. Obvious scribal errors –

typically eth for ‘d’, and thorn for ‘b’ – are corrected without comment. Semicolons

stand for the punctus elevatus.

IV Middle English Lyrics

English Lyrics of the Thirteenth Century, ed. Carleton Brown (Oxford, 1932). ‘Wynn’ in

Brown’s edition is reproduced as ‘w’, but ‘thorn’ and ‘eth’ are preserved.

Other editions have been consulted in conjunction with Brown’s work, as will be

referenced in the book.

Translations

In order to maintain consistency in terminology for affective stirrings, I have provided

my own tran